How To Run an “OWNERSHIP-DRIVEN” Developer Team

How to move your developers from “doing tickets” to owning outcomes.

… you are judged by outcomes you cannot fully influence.

– A stoic nightmare for many developers

Let me start with a confession.

For a long time, I played along in the feature factory game.

Different companies, different logos on the laptop, same pattern.

You sit on a “team,” but in reality, you are alone in your JIRA column.

You open your laptop in the morning, pull the next ticket, read the acceptance criteria, and start typing. In the standup, you say which ticket you are “on”. In the retro, you talk about “process”. In between, you hope that nobody asks you why this feature even exists, because honestly, you do not really know.

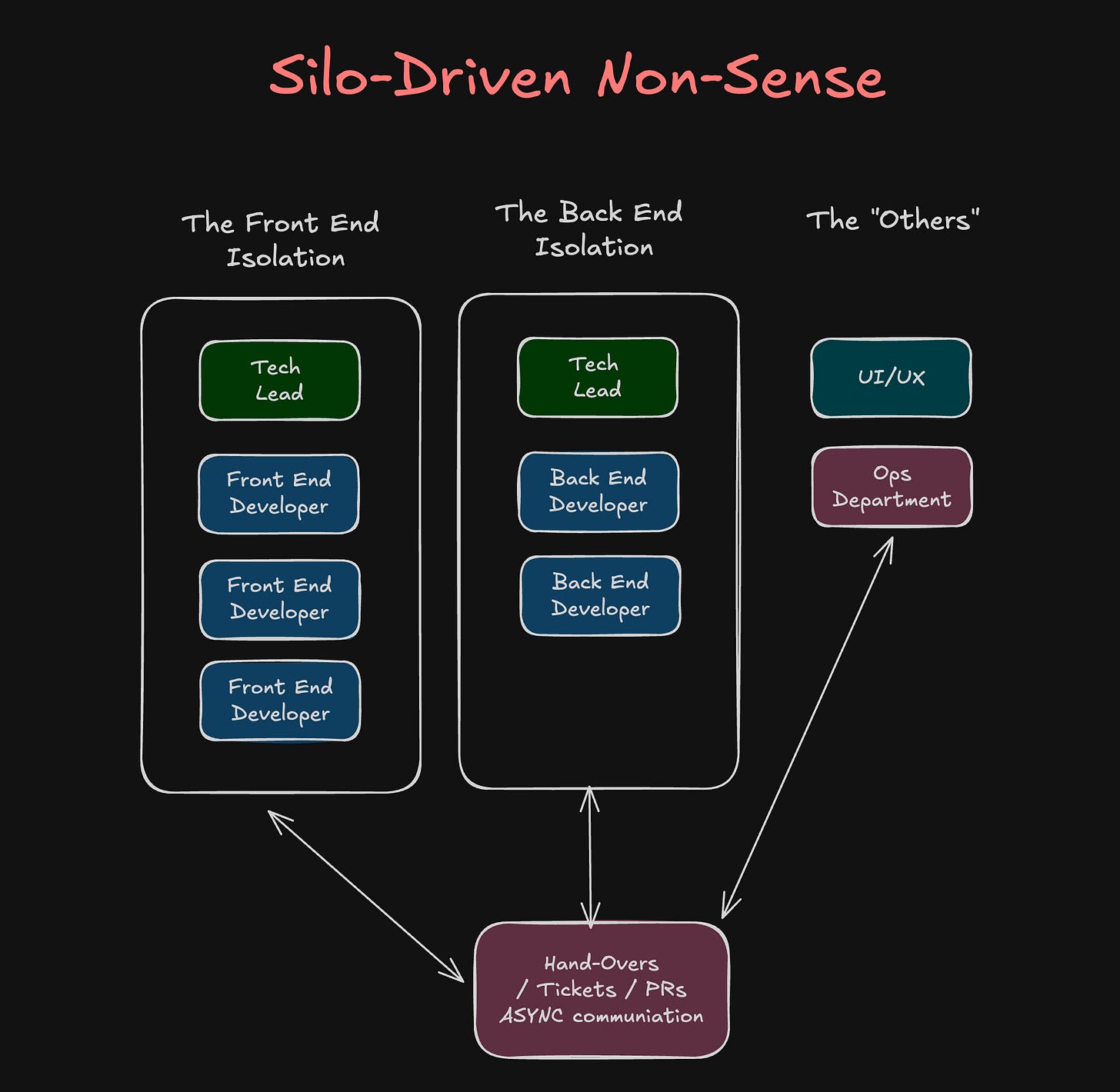

Developers are at the center of the delivery process, but are treated like a department.

Product is “over there”, ops is “over there”, and you are somewhere in the middle, a service provider with a GitHub account.

On the surface, it feels productive. Tickets move, burndown charts go down, the release notes are full. Inside, it feels strangely empty. You are responsible for bugs in production, yet you never really owned the decision that created them. You are responsible for estimates, yet you never shaped the scope. You are responsible for “velocity”, yet you never chose the destination.

From a Stoic perspective, this is the worst possible setup; you are judged by outcomes you cannot fully influence. Your mind lives in the outer circle of “no control”, while your calendar is filled with rituals that pretend you are in control.

At some point, I realised that this is not a people problem, it is a system problem.

The week that keeps repeating

In many of these journeys, there is a similar turning point.

A tech lead describes their world to me: cross-functional teams on paper, ticket factories in reality. Smart, motivated people, each working their own list. A culture that is “nice” but not truly honest. And one person in the middle who catches every escalation, who connects every dot, who cannot take a real holiday without paying for it later.

Then, almost by accident, something different happens.

A focused week. Everyone in the same place, fewer meetings, one clear mission.

“Let’s finally build this migration flow so customers can move into our product without pain.”

Or: “Let’s stabilise this checkout so we stop waking up at night.”

No 20-ticket backlog, no five parallel priorities. Just one problem that obviously matters.

And then I hear the same story again and again.

Design, frontend, backend, and ops sit together and start talking like owners. They look at real user journeys. They decide what they can realistically ship in a few days. They cut their own tasks instead of waiting for someone to write a “perfect” ticket for them. They deploy, watch what happens, and fix things. Within a surprisingly short time, there is something fundamental in production that actually helps a customer.

Same people. Same skills. Same product.

But for once, the system allows them to behave like owners.

When I speak with these tech leads afterwards, there is always this mix of excitement and frustration in their voice.

“This is how it should feel all the time.”

And my answer is always some version of:

“Yes. And the fact that it feels so different tells you how wrong your normal system is.”

The picture I keep drawing.

Because this pattern shows up so often, I started drawing the same diagram in almost every mentoring journey.

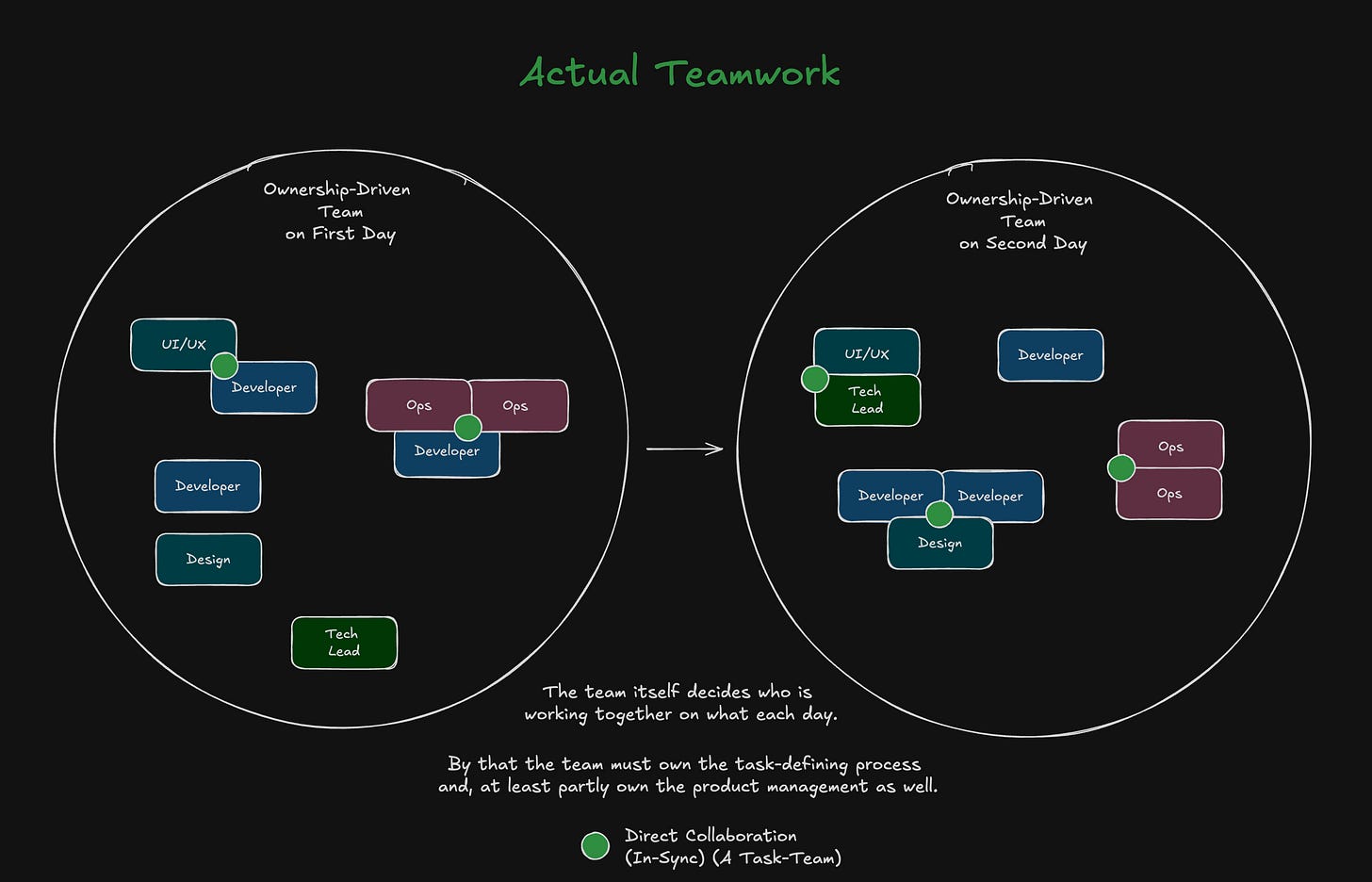

On the left, a circle that represents the “team on paper”. Inside, you see UI/UX, a couple of developers, ops, maybe a tech lead. It looks like a team, but if you zoom in on a regular Tuesday, everyone is working alone. Their work only touches on tickets, handovers, and status updates.

On the right, a circle with the exact same faces. But this time, there are small clusters all over the place. A designer and two developers sit together on the sign-up flow. Someone from ops pairs with a developer on deployment and monitoring. Another group focuses on the migration experience. Tomorrow, these clusters will look different because the focus of the work shifts.

The crucial thing is:

The team, not a manager, decides which groups are around which problem.

To make this shift from “left circle” to “right circle”, two changes are always necessary.

First, the work needs to be framed as a mission, not as a story.

“Implement ticket ABC-123” is not a mission. “Reduce failed sign-ups by 30 percent” is. “Make migrations so simple that a customer can switch in an afternoon without talking to support. Once that mission is clear, the team can cut their own tickets.

Second, the team must own the task-defining process and at least part of product management. They have to be present when the problem is understood, when trade-offs are made, when “good enough for this release” is defined. You cannot outsource thinking and then complain that people don’t think.

Every time we manage to get close to this pattern, those little green circles of collaboration appear: short, direct working sessions around real problems, across roles, with visible impact.

The tech lead’s real job

Across all these mentoring journeys, one theme is always there:

You cannot have an ownership-driven team while you still behave like the hero developer.

If you are the person who knows every critical piece of the system, who gets called into every serious incident, who quietly rewrites complex parts because “it’s faster if I just do it”, then your team never has a real chance to grow into ownership. Deep down, they know that you will catch anything important anyway.

I often use the same metaphor:

Right now, you are both the engine and the helm of the ship. You start the engine, and you steer it.

But the real job of a tech lead is to build a crew that can run the engine together, so that you can finally focus on steering.

That shift always requires the same ingredients.

Credibility. People must feel that when you say “I want you to own this”, you actually mean it. That you won’t punish every mistake. That you won’t talk about autonomy in the retro and then micromanage in the next planning. That you are willing to show your own doubts instead of pretending to be perfect.

Being a role model. If you want your team to care about the product, you have to care visibly. You ask about the user journey, not just about points. You open dashboards and logs, not just JIRA. You learn from incidents instead of hunting for culprits. People copy what you do, not what you say.

A clear direction. In every mentoring journey, there is a moment where we clean up the story. What product are you actually building? For whom? What is the next meaningful step on that path? If your team cannot tell this story in their own words, ownership will collapse into local optimisation and politics.

And the courage to challenge. Ownership is not comfortable. It means making decisions under uncertainty, putting your name behind changes, and facing the realities of production. Your job is not to keep everyone cosy; your job is to create a level of challenge that stretches people without breaking them. Protection and challenge, both at once.

Stoicism as the operating system

Under all of this sits a very old idea: the Stoic circles of control.

There are things you can control directly.

There are things you can influence.

And there are things you simply have to accept.

Most feature factories force developers to live in the outer circle. They complain about deadlines, about stakeholders, about roadmaps written in distant rooms. At the same time, they have surprisingly little influence over their own delivery system: the pipeline, the quality strategy, and incident handling.

In my work with tech leads, we try to flip this.

Give the team absolute control over how they build and ship:

How they test, how they deploy, how they monitor, how they handle problems.

Make visible where they have influence on the product and roadmap, and where they do not.

Be brutally honest about the constraints that are currently non-negotiable, so that they can stop wasting emotional energy on them.

“You have power over your mind, not outside events; realise this, and you will find strength,” Marcus Aurelius wrote.

As a tech lead, you go one step further: you design the environment so that your developers can actually experience this, not as theory in a quote, but as reality in their week.

How to start, next Monday

If any of this feels familiar, you do not need a year-long transformation program to begin. You can start with something tiny, something I keep coming back to with almost every tech lead I work with.

In your next standup, do not start with ticket numbers.

Ask instead:

“What is the one problem you are owning this week, and who are you owning it with?”

If there is no clear answer, you just learned something important about your system.

Pick one outcome for this week that actually matters to a customer or to the stability of your product. Only one. Talk about that outcome with your team. Ask them how they would approach it, which skills need to work together on it, and what they need from you to own it end-to-end.

Then stay close, but resist the reflex to take the work back as soon as it gets messy. Let them stay with the problem, feel the uncertainty, make decisions, and see the impact on production.

At the end of the week, sit together and ask two questions:

Where did we give away ownership?

Where did we take it back?

Write down what you hear. Choose one thing to improve next week. Repeat.

This sounds too simple, but over a series of weeks, it changes how people see themselves.

The ownership-driven developer

For the individual developer, this path is both scary and deeply satisfying.

You lose your hiding places. You can no longer say “the spec was wrong” if you helped write it. You can no longer blame “ops” for the deployment if you were in the room when you pushed the button. You are part of the whole story now: problem, decision, implementation, production, learning.

But you gain something in return that I see again and again in these journeys: pride.

Not ego, not titles, but the quiet knowledge: “I actually own this. What I do here matters.”

Epictetus put it this way:

“First say to yourself what you would be; and then do what you have to do.”

If you decide that you want to be an ownership-driven developer or tech lead, do not wait for the organisation to officially approve this. Start small. Take one ticket and rewrite it as a problem in your own words. Pull another person into it and own it together, from idea to production. Ask a different question in your next standup.

I have walked this road with enough tech leads now to know;

Feature factories don’t vanish because of new frameworks or new tools.

They vanish quietly when enough people start behaving like owners, and a few brave leaders decide to design the system accordingly.

—Adrian

We were talking with Denis Čahuk & Bryan Finster about this topic. Here you find the whole recording.

Spot on, Adrian. This is how motivation really works. Give people pride, confidence, and influence – and they’ll move mountains. It’s incredible how quickly job satisfaction – and retention – improve when developers stop “doing tickets” and start owning outcomes. Strong piece.